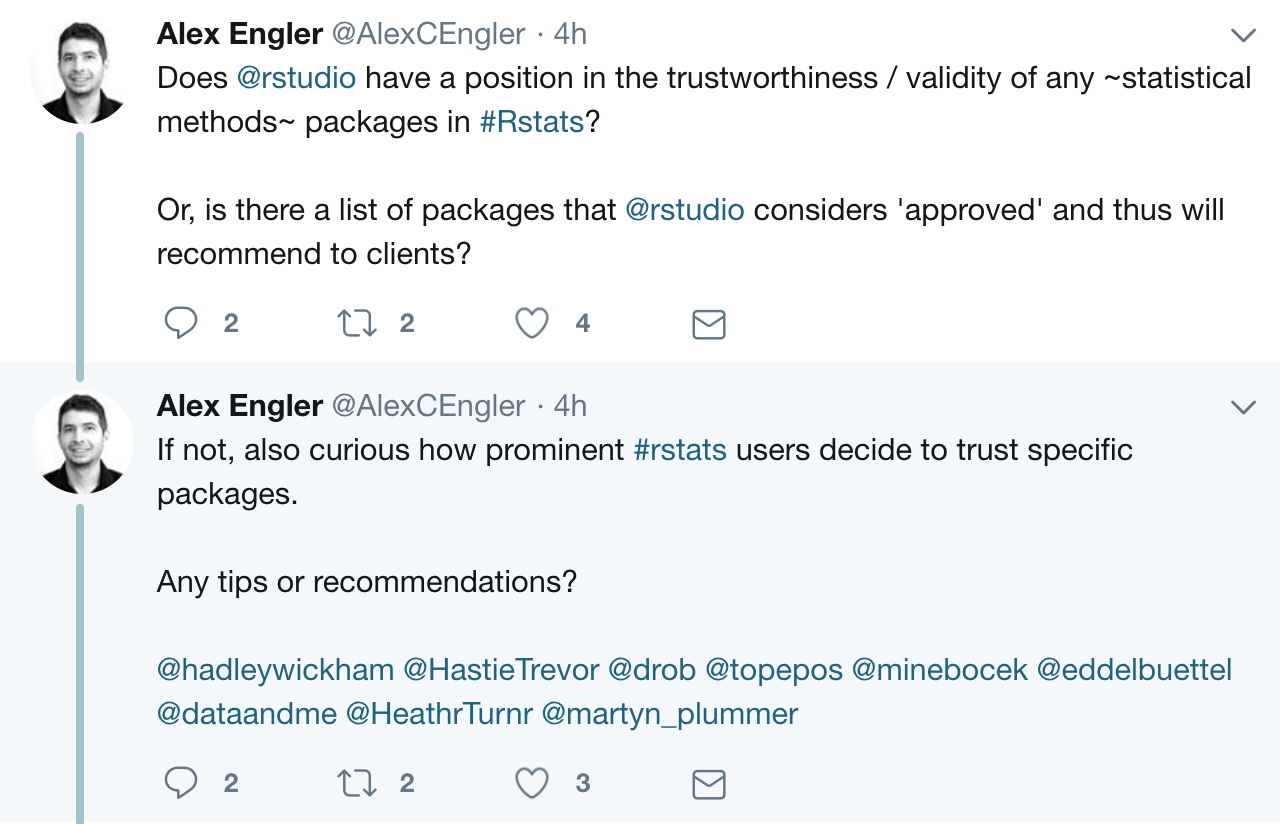

I’m not on that list, but I do have reckons anyway.

First, there are really two questions: is the method useful to you, and is the implementation doing it the way you want?

The first question is important. There’s no benefit in having a well-coded implementation of the Shapiro-Wilk test unless you have a good reason to use the Shapiro-Wilk test1. The first question is not a coding question, but the answer is similar to the answer for the coding question.

Good reasons to use a particular method include:

- everyone does it (standards are valuable in reducing communication costs)

- someone you trust uses it, or recommends it in a review paper

- someone you trust proposed it

- you’ve read the paper that proposed it, and the math and/or examples were convincing

- it’s been around a while and doesn’t seem to give unreasonable results

- you’ve worked out the math yourself and it makes sense

For packages:

- everyone uses it (standards are valuable in reducing communication costs)

- someone you trust wrote it

- someone you trust recommends it

- you’ve read the paper that proposed it and the simulations and/or examples were convincing

- it’s been heavily downloaded for a while and has a reasonable selection of tests

- you’ve run it in simulations where it gives good results

Naturally, the higher the stakes, the more effort it’s worth putting into checking up on the implementation – and on the method.

In addition to peer-reviewed journals such as Journal of Statistical Software and Journal of Open-Source Software, there was at least one attempt at crowd-sourcing information on package use and reliability. Sadly, crantastic! didn’t get enough users to be really helpful

When talking about trust, one important caveat is whether the package (or the method) has been used in situations similar to the one you want to use it in. I’ll give two historical examples.

The first, minor, one is the leaps package in R, which I made over twenty years ago by wrapping Fortran 77 code written by Alan Miller. As I wrote a couple of years ago, the context for forward and backward selection has changed since then, and the package was giving answers that were correct as designed, but not what people nowadays expected.

The second one caused wailing and gnashing of teeth in the air pollution community in 2002. The gam software in S-PLUS would have satisfied all the criteria for being reliable and trusted. It had recently been introduced into air pollution epidemiology as an improved way of doing high-pass filtering– stripping out the longer-term covariation in pollution and deaths that would be contaminated by confounding, in order to see very small effects of pollution.

Unfortunately, the default convergence settings weren’t stringent enough, and an approximation used in getting standard errors wasn’t good enough in the air pollution time series setting. Even more unfortunately, this was discovered shortly after the deadline for research to be considered in setting the new particulate air pollution standards. Everything was fixed, but it was a stressful time even for statisticians who were just in the same field. The reason a natural reliance on the developers of gam didn’t work, was that the situation was different from prior examples: models with a lot more wiggles, much smaller effects, and a larger computational budget all meant that the appropriate settings and approximations were different.

you don’t↩