It’s an interesting question, but the implication of wasted depends not just on the actual statistics about package survival (which we’ll get to), but on why people write packages. And, I suppose, on why they should write packages.

One reason people write packages is to improve other people’s data analysis, certainly. But it’s not the only reason, nor should it be. People write packages to provide reference implementations of new statistical methods. We write packages to try out and discuss programming ideas. We write packages to learn about writing code. And we write packages for fun. The first aim depends on medium-term stability, and to some extent the second does as well. The others don’t necessarily.

The last two reasons are fairly self-explanatory. As an example of packages as discussion/research, consider all the work done by Duncan Temple Lang on embedding R in everything and everything in R, back at the start of the century. You can’t even find most of the source code, let alone run it. Even at the time, getting it to run on many systems was a bit tricky, but Duncan’s work informed the discussion on embedding and interfaces for years. The packages might have been more useful if they had been maintained in the long term, but it’s not clear – what is clear is that it would have taken a lot of (potentially wasted) effort to do so.

An example that falls across multiple categories is Hadley Wickham’s sequence of packages reshape, reshape2, plyr, and dplyr for data restructuring. These were intended to be useful and used right from the start, but they also represent a development of ideas on tidy data and on the right abstractions for manipulating it.

My package bigQF explores efficient ways of evaluating tail probabilities for quadratic forms. I don’t expect it to stop working, but its main purpose in life is to have components extracted and repurposed inside other packages for rare-variant genetic epidemiology. It’s aimed at developers, not at users.

My svylme for mixed models on survey data has a less clear future. It’s experimental: the best algorithms, estimators, and user interface are all unclear at the moment. The code will continue to be developed and supported, but it may well end up inside the survey package, in which case the svylme package will be left to wither away on its own.

One of the problems caused by having all these reasons is that it’s less obvious to the user which category a package is in. But we can at least consider the thousands of CRAN packages as having some sort of intended commitment to long-term existence. It’s not hard to get a package on CRAN, but CRAN runs daily package checks, and packages that stop working get removed fairly rapidly.

How long, then, do CRAN packages last?

First, we need all the packages

library(dplyr)

library(httr)

library(xml2)These are currently available

cran<-available.packages()And these are all the packages that have been taken off CRAN, either to make way for a new version, or because they broke or were orphaned.

archived<-GET("https://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/")This code extracts the package names from the HTML

archived_pkg<-xml_find_all(content(archived), "//body/table/tr/td/a")

archived_list<-as_list(archived_pkg)[-1]

length(archived_list)## [1] 12037archived_names<-sapply(archived_list, function(x) sub("/","",x[[1]][[1]]))

archived_names<-setdiff(archived_names, "README")So, first: how many packages ever on CRAN have been dropped

cran_names<-rownames(cran)

length(setdiff(archived_names,cran_names))## [1] 2009Out of how many?

length(union(archived_names, cran_names))## [1] 15372Not a very high fraction.

As statisticians, we’d like a survival analysis. This means getting all the archive dates. I’m going to use the Auckland CRAN archive because it’s close. Yes, it’s a for loop. That’s because when a long-running for loop breaks in the middle I can easily see where it got up to and whether it got the earlier entries right.

all_archives<-vector("list",length(archived_names))

for(i in seq_len(length(archived_names))){

pkg<-archived_names[i]

all_archives[[i]]<-tryCatch(

GET(paste0("https://cran.stat.auckland.ac.nz/src/contrib/Archive/",pkg,"/")),

error=function(e) list(NULL)

)

} Now, extract dates for archived versions

all_dates<-vector("list",length(all_archives))

for(i in seq_len(length(all_archives))){

pkg<-all_archives[[i]]

if (is.null(pkg))

all_dates[[i]]<-as.Date(character(0))

else{

txt<-unlist(as_list(xml_find_all(content(pkg), "//body/table/tr/td")))[-(1:3)]

n<-length(txt)/3

all_dates[[i]]<-as.Date(txt[(1:n)*3-1], format="%d-%b-%Y")

}

}

arch_dates<-data.frame(pkg=archived_names, first=sapply(all_dates,min),latest=sapply(all_dates,max))Get the current package dates from CRAN again (because available.packages() doesn’t give them)

cran_table<-GET("https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/available_packages_by_date.html")

cran_list<-as_list(xml_find_all(content(cran_table,"parsed"),"//body/table/tr"))[-1]

cran_dates<-data.frame(pkg=sapply(cran_list, function(x) x[[3]]$a[[1]]),

date=sapply(cran_list, function(x) as.Date(x[[1]][[1]]))) Now combine the two sets of dates

all_dates<-merge(cran_dates,arch_dates,by="pkg",all=TRUE)

all_dates$current<-with(all_dates, ifelse(is.na(date),latest,date))

all_dates$enter<-with(all_dates, ifelse(is.na(first),date,first))What counts as ‘now’ for the survival analysis? The last time packages were dropped from CRAN is too early; the last time they were added is too late; these only differ by three weeks, so we won’t worry too much. We need to add 1 because packages can only be dropped after they are actually added. In fact, we should add more than 1 for recent packages, because it’s going to take a few weeks at least to drop a new package. But it’s not worth worrying more given the time scales we’re working with.

all_dates$now<-max(all_dates$date,na.rm=TRUE)+1

all_dates$dropped<-is.na(all_dates$date)

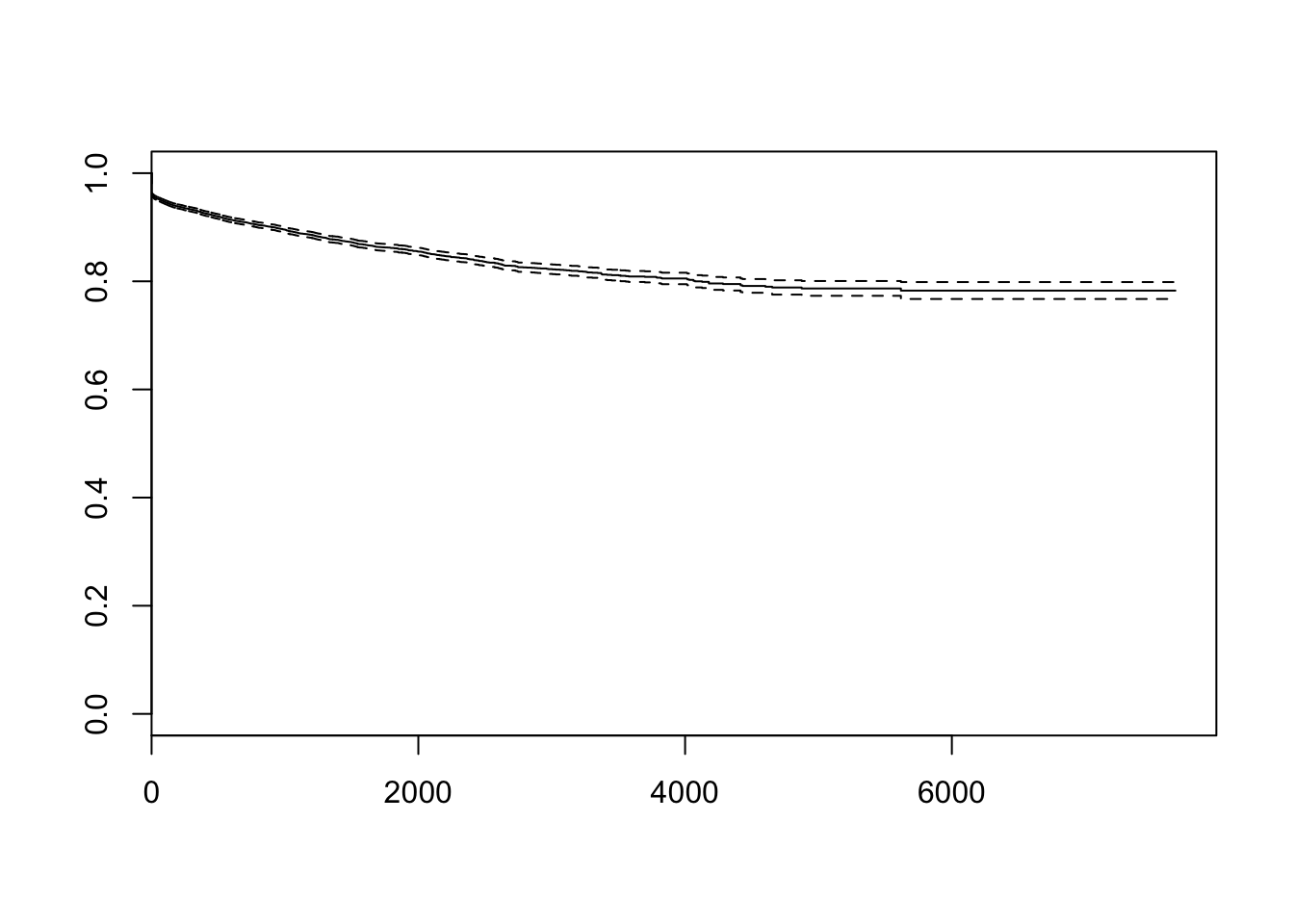

all_dates$stop<-with(all_dates, ifelse(dropped, current, now))Here’s the overall survival curve for packages on CRAN: there’s an initial drop-off of a few percent, but most packages last a long time.

library(survival)

pkg_srv<- survfit(Surv(stop-enter,dropped)~1,data=all_dates)

plot(pkg_srv)

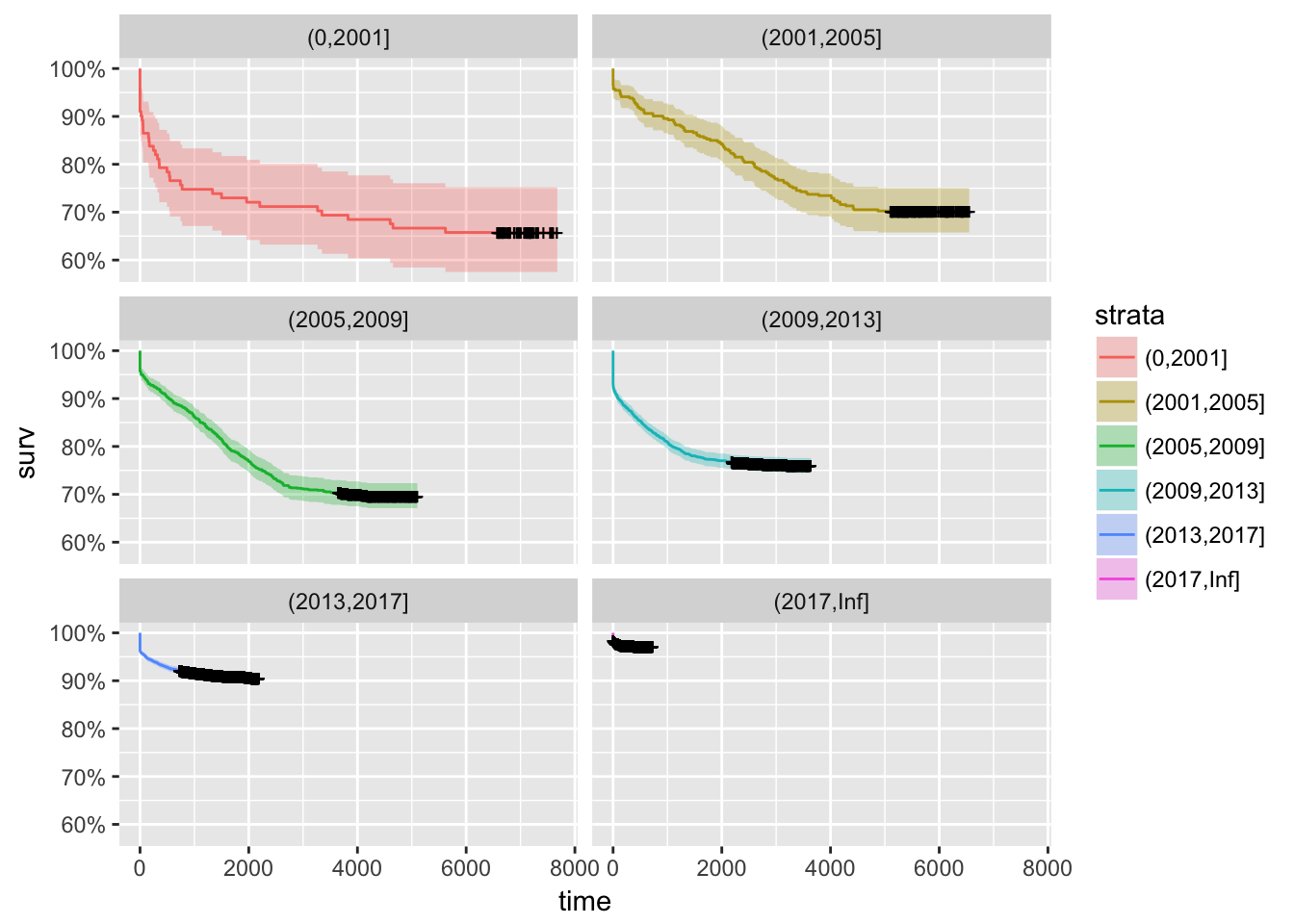

Now, this might have changed over the years Perhaps in the Good Old Days we made packages to last for ever, but kids these days write packages that are flaky and liable to vanish at any moment?

library(survival)

library(ggplot2)

library(ggfortify)

all_dates$years<-cut(all_dates$enter%/%365+1971,c(0,1997+4*(1:5), Inf))

pkg_srv<- survfit(Surv(stop-enter,dropped)~years,data=all_dates)

autoplot(pkg_srv,facet=TRUE,ncol=2,scales="fixed")

It’s actually the other way around. In the early days there were more short-lived packages: the language and the community were changing more rapidly, so this makes sense.

We get the same picture from Cox models

coxph(Surv(stop-enter,dropped)~years,data=all_dates)## Call:

## coxph(formula = Surv(stop - enter, dropped) ~ years, data = all_dates)

##

## coef exp(coef) se(coef) z p

## years(2001,2005] -0.235 0.790 0.188 -1.25 0.21

## years(2005,2009] -0.157 0.855 0.171 -0.92 0.36

## years(2009,2013] -0.266 0.767 0.168 -1.59 0.11

## years(2013,2017] -1.092 0.335 0.170 -6.44 1.2e-10

## years(2017,Inf] -1.847 0.158 0.189 -9.80 < 2e-16

##

## Likelihood ratio test=506 on 5 df, p=0

## n= 15433, number of events= 1898Over all, the two decades of CRAN aren’t long enough to tell us what the median survival time is for packages. Or even the first quartile. But, to the extent that there’s a trend, CRAN packages written in recent years are less likely to disappear than those written in the past were (at the same age).

And, finally

The suggestion that people are ‘wasting’ time working on statistical computing is going to attract a less calm and more negative response than one might naively expect. That’s because so much academic statistical computing has been described, so often, as a waste of its developers’ time. R itself has certainly not been exempt from this.