Attention Conservation Notice: while this probability question actually came up in in real life, that’s just because I’m a nerd.

“Secret Santa” is a Christmas tradition for taming the gift-giving problem in offices, groups of acquaintances, etc. Instead of everyone wondering which subset of people they should give a gift to, each person is randomly assigned one recipient and has to give a gift (with a relatively low upper bound on cost) to that one person. The ‘Secret’ part is that you don’t know who is going to give you the gift.

It’s not completely trivial (though it’s not that hard) to come up with a random process that assigns everyone exactly one recipient and ensures that no-one is left finding a gift for themselves. One procedure is to sample recipients without replacement to get a list that’s guaranteed to be one-to-one, and then just repeat the sampling until you get an allocation where no-one is assigned themselves.

So, a probability question: how likely is it that a random permutation will have ‘collisions’ where someone is their own Secret Santa? Or, equivalently, how many tries would you expect to need to get a working allocation? Does it depend on the number of people \(n\)? What about for 3600 people, as in the scheme hosted by NZ Post on Twitter.

I knew the answer, but I didn’t know a proof, so this is a reasonably honest exploration of how you might find the answer.

First, is there some simple bound? Well, the chance that you, Dear Reader, get assigned yourself is \(1/n\), so the simple Bonferroni bound is \(n\times 1/n\). That doesn’t look very helpful, because we already knew 1 was an upper bound; this is a probability. However, we can recast the Bonferroni bound as the expected number of collisions. If the expected number of collisions is 1, then it’s reasonable to expect that the probability of no collisions is appreciable, and that as \(n\) increases it converges to some useful number that isn’t 1 or 0. At this point, if you had to make a wild guess, a reasonable guess would be that the number of collisions has approximately a Poisson distribution for large \(n\), so that the probability of no collisions will be approximately \(e^{-1}\).

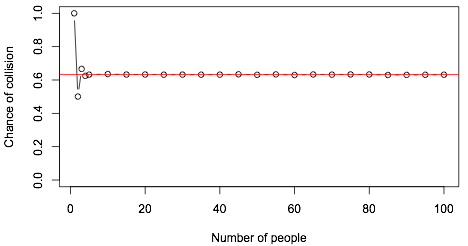

Next, try simulation. Doing \(10^5\) replicates in R gives

The probability is 1 if you try to do this by yourself, 1/2 if you have one friend, and converges astonishingly quickly to a fixed value. The red line is \(1-e^{-1}\).

Now, can we prove this? The collisions aren’t independent, so we can’t quite just use a Poisson or Binomial argument. We could try the higher-order Bonferroni bounds, eg

\[P(\cup\_i A\_i)\geq \sum\_i P(A\_i) - \sum_{i,j} P(A\_i\cap A\_j).\]

The second-order bound gives \(n\times 1/n-{n\choose 2}\times 1/n^2=1/2\), so we’re making progress. The third-order bound gives

\[n\times 1/n-{n\choose 2}\times 1/n^2+{n\choose 3}\times 1/n^3=1-1/2+1/6=4/6\]

We’re definitely making progress now, and these bounds look suspiciously like the values of the probability for \(n=1,\,2,\,3\). Continuing the pattern, we will end up with

\[\sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k+1}{n\choose k} n^{-k}=\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^{k+1}}{n^{-k}}\]

Comparing that to the infinite series for \(\exp(x)\), it’s \(1-e^{-1}\). What we haven’t got this way is whether the number of collisions is Poisson, which was where the guess originally came from. This seems to be a lot harder.

First, simulation confirms that the Poisson is a good approximation. That’s reassuring: it’s typically easier to prove things that are true than things that are not true.

I should next say that I spent quite a long time looking for ‘coupling’ arguments to show that this assignment method gave the same large-sample distribution as some other assignment method that was obviously Poisson. I didn’t get anywhere with this, but it’s a fruitful approach for problems similar to this one. Since that didn’t work, we’re back to combinatorics.

Now, suppose we have 1 collision. That means we have an assignment of the \(n-1\) other people with no collisions. So, the number of ways to have 1 collision in \(n\) people is \(n\) times the number of ways to have no collisions in \(n-1\) people. Since the number of permutations of \(n\) people is also \(n\) times the number of permutations of \(n-1\) people, the fraction of permutations with 1 collision in \(n\) people is the same as the fraction of permutations with 0 collisions in \(n-1\) people, ie, for large \(n\) it’s \(e^{-1}\). That agrees with the Poisson formula, so we’re definitely making progress.

If we have \(k\) collisions in \(n\) people then we have a set of \(n-k\) people with no collisions. The number of ways we can have \(n-k\) people with no collisions is about \((n-k)!e^{-1}\) and the number of ways to pick the \(k\) people who have to buy themselves gifts is \({n\choose k}= n!/(k!(n-k)!)\). So, the number of ways of having \(k\) collisions in \(n\) is about \(n!e^{-1}/k!\), and the probability of this is \(e^{-1}/k!\), matching the Poisson distribution. We’ve done it!

Ok. Technically we’re not quite done, since we’d need to show the approximation error in the argument actually gets smaller with increasing \(n\). But we’re done enough for me.

PS: If you want an easy way not to have to worry about collisions, just arrange the people in random order and assign each person the following person in the list (with the last person being assigned the first).