Fisher’s famous ‘iris’ data set is a convenient example because it’s small and low-dimensional and has very marked differences between groups. These characteristics also make it a bad example (edit: at least for modern machine learning), because the behaviour of small, low-dimensional classification problems is a very poor guide to the behaviour of large or high-dimensional ones.

That’s all obvious. What’s less well known is that the data set is an example of pseudocontext in education. You give the students the data set, emphasising that these are real measurements (though perhaps not bothering to tell them where the Gaspé Peninsula is, or to show them pictures of the flowers). You tell the students that this is a classification (supervised-learning) problem: the goal is to come up with a rule to classify future iris specimens. Or you drop the ‘species’ variable and make it a clustering (unsupervised learning) problem to work out the species.

None of that is what Fisher or Anderson wanted. Anderson, writing about ‘The Species Problem in Iris’, says that there are many distinguishing characteristics in the field, but that the flowers aren’t any use in identifying dried specimens because they shrivel up:

Perianth dimensions from herbarium material are completely unreliable in these species, and for that reason have been largely omitted from the keys and descriptions

The reason Anderson and Fisher wanted statistical analysis of the data was to address the hypothesis that Iris versicolor was a hybrid of the other two (rather than the differences from Iris virginica having accumulated by many mutations over a long period). The numbers of chromosomes were right for this explanation, and there were other supporting factors. He argued that Iris versicolor should be intermediate between the other species, and that it should be twice as far from Iris setosa as from Iris virginica

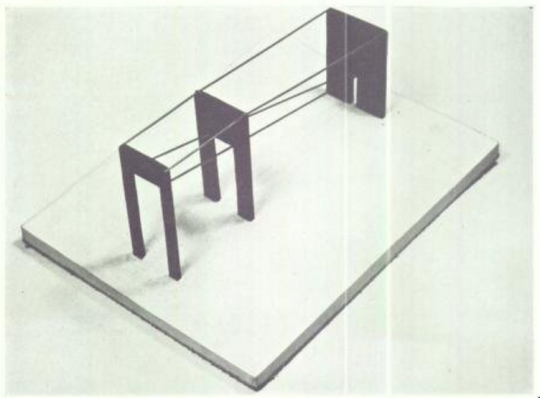

Anderson’s paper included this example of multivariate data visualisation to demonstrate the goodness of fit of the hypothesis

Fisher described the problem similarly

It is of interest in association with I. setosa and I. versicolor in that Randoph (1934) has ascertained and Anderson has confirmed that, whereas I. setosa is a “diploid” species with 38 chromosomes, I. virginica is “tetraploid”, with 70, and I. versicolor, which is intermediate in three measurements, though not in sepal breadth, is hexaploid. He has suggested the interesting possibility that I. versicolor is a polyploid hybrid of the two other species. We shall, therefore, consider whether, when we use the linear compound of the four measurements most appropriate for discriminating three such species, the mean value for I. versicolor takes an intermediate value, and, if so, whether it differs twice as much from I. setosa as from I. virginica, as might be expected, if the effects of genes are simply additive, in a hybrid between a diploid and a tetraploid species.

After some analysis he found

The differences do seem, however, to be remarkably closely in the ratio 2 : 1. Compared with this standard, I. virginica would appear to have exerted a slightly preponderant influence. The departure from expectation is, however, small, and we have the material for making at least an approximate test of significance

So, in summary, Anderson and Fisher said

Accurate multivariate flower dimensions are not necessary for discriminating these species in the wild

- Accurate multivariate flower dimensions aren’t available in preserved specimens

However, the measurements do allow a fairly clear test of a specific genetic hypothesis

Now that actual genetic information can be measured, it’s possible to confirm that Anderson was right

These data confirm Anderson’s hypothesis that I. versicolor is an allopolyploid involving progenitors of I. virginica and I. setosa. The number of 18–26S rDNA loci in I. versicolor is similar to that of progenitor I. virginica, suggestive of a first stage in genome diploidization. The locus loss is targeted at the I. setosa-origin subgenome, and this is discussed in relation to other polyploidy systems.

This sort of promiscuous hybridisation and chromosome doubling is common in crop plants – a fact that’s important in modern agricultural genetics, since it makes the assembly phase of genome sequencing much harder. The real story of the iris data is more interesting than the discrimination problem. And it’s true.