Inigo Montoya: He’s dead. He can’t talk.

Miracle Max: Whoo-hoo-hoo, look who knows so much. It just so happens that your friend here is only MOSTLY dead. There’s a big difference between mostly dead and all dead. Mostly dead is slightly alive.

In the cardiovascular-research trade, there’s a minor but persistent issue of nomenclature. When your heart stops beating and you fall over dead, should that be called “Sudden Cardiac Death” or “Sudden Cardiac Arrest”? The case for the former is obvious; the case for the latter is basically that it sounds insufficiently serious when you then talk about the small fraction of ‘non-fatal sudden death.’

My colleagues in Seattle have one of the largest cohorts of people who have survived sudden cardiac death, largely because Seattle has one of the best survival rates for sudden cardiac death of anywhere in the world. It’s roughly 10% – but in the subset of people who have ‘Bystander Witnessed VF/VT Due to Heart Disease’ it’s about 50% who leave hospital alive, and it keeps getting better.

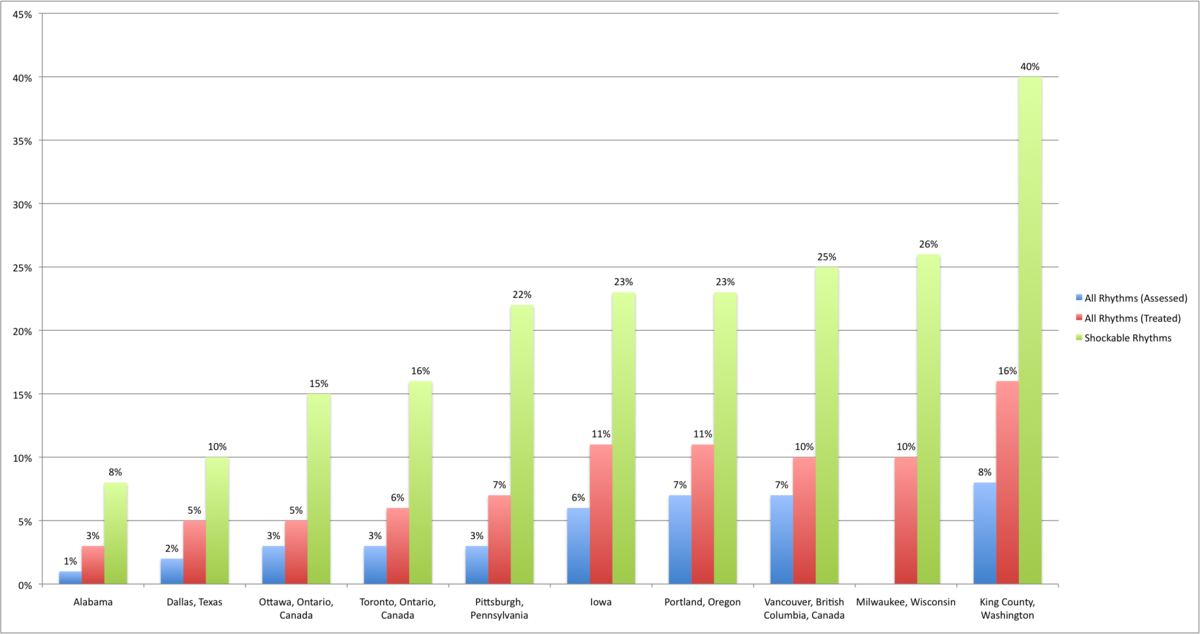

Here’s a slightly outdated comparison across cities (for 2008), from Wikipedia

In the wake of the Bunnings defibrillator controversy, it’s worth looking at how Seattle/King County does this. There are two components: very widespread training in CPR (50% of the population have had a CPR course) and an ambulance service funded to provide rapid support (including defibrillation) from paramedics trained in the latest techniques.

In the wake of the Bunnings defibrillator controversy, it’s worth looking at how Seattle/King County does this. There are two components: very widespread training in CPR (50% of the population have had a CPR course) and an ambulance service funded to provide rapid support (including defibrillation) from paramedics trained in the latest techniques.

Both components are important: CPR is rarely enough to revive you, but it can keep you only mostly dead while you wait for the ambulance. Defibrillation has a good chance of rebooting your heart as long as it’s in one of the ‘shockable rhythms’ – the heart muscle cells are contracting properly, but not in the coordinated fashion needed to pump blood. The chance of this goes down rapidly with time, but with CPR it only deteriorates about half as fast.

An automatic defibrillator won’t do as well as a paramedic with 2000 hours of training, but it won’t do any harm. It won’t shock someone with a proper heartbeat, and (less importantly) it won’t give a shock if the heartbeat is flatlined or otherwise not fixable electrically. You don’t want to rely on it, but it’s a good stopgap until the professionals arrive.

In a perfect world it’s probably more cost-effective to train more people in CPR and to shorten ambulance response times – as Leonard Cobb and Mickey Eisenberg did in Seattle – because cardiac arrests can happen anywhere and it’s hard to get good coverage of defibrillators. But if you’ve got a defibrillator available, refusing to allow it to be used seems, well, heartless.