Well, obviously I don’t know how complicated you think it is, but it’s more complicated than I thought, and more complicated than my colleagues thought.

In a case-control design you sample all the cases () and a fraction of the controls () from a cohort. You could fit a logistic regression with sampling weights ( for cases, for controls). Or, you can fit an unweighted logistic regression, which should be biased except that all the bias ends up in the intercept term and doesn’t affect the regression coefficients.

The unweighted analysis is maximum likelihood, so you’d expect it to be fully efficient (and it is). The weighted analysis is typically not fully efficient. Lots of people will tell you that the loss of efficiency is due to the variation in the weights, which makes sense but is not actually true.

When you have a regression model with weighted and unweighted estimators both consistent for the same parameters, it’s true that the loss of efficiency from weighting basically just depends on the coefficient of variation of the weights. There are two ways we can tell this isn’t what’s happening with case-control logistic regression. The first is that the unweighted estimator is fully efficient in some situations: eg, in a saturated model, or when all the regression parameters are zero. The second is that the weighted and unweighted estimators aren’t actually consistent for the same thing, it’s just that the bias is in the intercept term. The inefficiency of weighted estimation for case-control logistic regression is real, but it isn’t simple.

Another aspect of efficiency being more complicated than you would probably think is multiple imputation. Suppose you have a single continuous covariate , with Normal distribution in controls and a (different) Normal distribution in cases. Suppose you impute for non-sampled controls using for sampled controls multiple times to give multiple full cohorts, and do the Rubin analysis. Does this give the same efficiency as weighted logistic regression on the sample or as unweighted logistic regression on the sample?

Both.

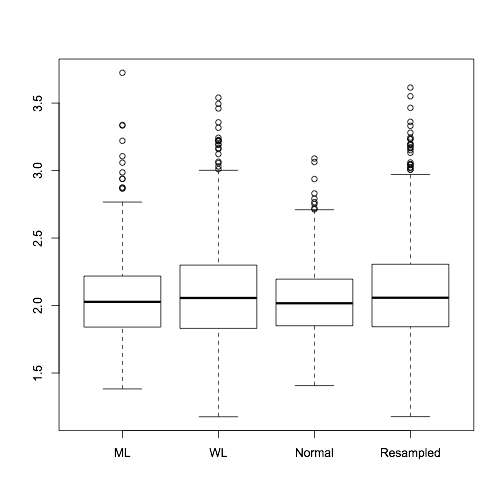

In the boxplots above, based on 1000 simulations with 100 cases and a cohort of 1000, “ML” is the unweighted logistic regression coefficient, “WL” is the weighted logistic regression coefficient, and the other two are both multiple imputation. The “Normal” box imputes for non-sampled controls from with and the mean and variance of in sampled controls. The “Resampled” box imputes non-sampled controls by resampling from sampled controls (aka hot-deck imputation).

Imputing with the Normal distribution gives essentially full efficiency; hot-deck imputation gives essentially the same efficiency as weighted estimation. If you could see this coming, you get a gold star.

Once I saw this, I could work out why it happened. It isn’t quite the issue of models for imputation and analysis being ‘compatible’ or ‘congenial’ – the distribution of the imputed by hot-deck imputation converges uniformly to the true distribution of – but it’s a sort of second-order version of the same thing.

The extra information used by the maximum likelihood estimator that isn’t used by the weighted estimator comes from the relationship between the case and control densities of , especially in the tails. Resampling from control loses the case information, but since the control distribution actually is Normal, the parametric imputation gets this information back. The Right Thing is to impute from a mixture of the control distribution and an exponentially tilted version of the case distribution, but to do this you need to know the true parameter value so it’s an iterative process and involves different iterative sets of imputations for each model you fit.