Genome-wide association studies involve lots of analyses. Nearly always they involve lots of tests. Also, in contrast to gene expression studies or to state-specific estimates of political attitudes or small-area disease rate estimates, a lot of the null hypotheses are effectively true. That is, most single-nucleotide polymorphisms are so close to not having any effect on anything that we might as well call it zero. Most people express this in terms of the need for stringent Type I error control; Bayesians like Matthew Stephens might talk in terms of the very low prior probability of a non-negligible effect.

An obvious strategy is to prefilter the SNPs to cut down on the number of tests. You might pick SNPs in or near genes. Among those in genes you might pick non-synonymous variants. Among those, you might pick mutations in sites that are strongly evolutionarily conserved or ones that should have a big effect on protein structure. Or you might get really specific and just look at mutations that are predicted to cause complete loss of function. These all make sense, but they don’t work as well as you might think, for a simple mathematical reason: gets very, very small very fast with increasing .

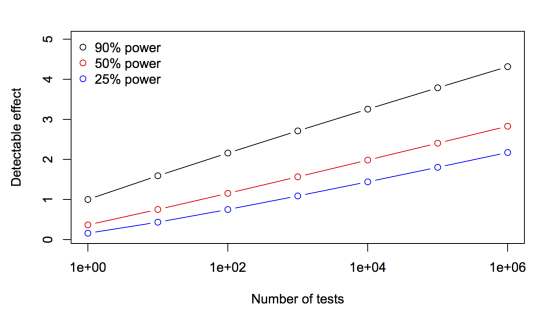

This graph shows the effect size detectable after Bonferroni correction to p-values, relative to 90% power and a single test.

A million tests at 90% power takes you to an effect size a bit above 4. The halfway point, an effect size of about 2, happens before 100 tests, and an effect size of 3 is at a few thousand tests. Prefiltering by 99.9% means that you need about half the sample size you’d need with no prefiltering. This is just one of the examples where intuition based on the shoulders of the Normal distribution breaks down in the tails.

If the Normal tail probabilities didn’t fall off this fast, GWAS wouldn’t be feasible at all: you couldn’t take five cohorts with good power for one test and combine them to get a consortium with moderate power for a million tests. The penalty for doing a million tests is surprisingly small; correspondingly, the benefit for not doing a million tests is also surprisingly small.