From Fox

Each poll has a different margin of error, and averaging requires a distinct test of statistical significance. Given the over 2,400 interviews contained within the five polls, from a purely statistical perspective it is at least 90% likely that the tenth place Kasich is ahead the eleventh place Perry.

The Upshot blog at the New York Times correctly points out that if this is a p-value, that’s not the way to interpret it.

As anyone who has ever taken an introductory statistics course can attest, this is not what a test of statistical significance reveals. Significance tests answer a somewhat different question: If Mr. Perry and Mr. Kasich actually have an equal number of supporters, then how unlikely is it that the polls would reveal a difference that is this large?

They go on to say

Mathematically, there does exist a prior that allows statistical significance tests to be interpreted as probabilities. It’s the prior that anything can happen, and everything is equally likely.

For the p-value to exactly match the posterior probability that’s true, but for it to approximately match it’s enough that the prior is locally flat – that it’s flat over the range of values reasonably consistent with the data. In this case, that’s saying that our prior knowledge about the relative popularity of Kasich and Perry is much weaker than this set of polls.

More importantly, though, what is this 90%?

We have a difference between 3.2% and 1.8% based on an unweighted average of five polls with sample sizes 710, 475, 500, 423, and 353. The standard error of the estimated difference will be about 0.45%. The difference is about three standard errors. Where does 90% come from?

Fox isn’t clear about how they did the computations, but the p-value for a two-candidate comparison is about 0.01. A Bonferroni correction for doing 10 tests comparing adjacent candidates, or 10 tests comparing Perry to the candidates in the debate would basically explain it. But if you’re interested in posterior probabilities for Kasich vs Perry (or for whoever is just above the line vs whoever is just below the line), you don’t need the factor of ten. Well, you never need the factor of ten, but in other circumstances you might need something.

We can do the Bayesian calculation right(ish). At these sample sizes the likelihood can be treated as Normal and at these low support ratings we can ignore the negative correlation between candidates. I used a Normal prior and Normal likelihood for the difference of the logit of the support percentage, to allow for diffuse priors that still stay non-negative.

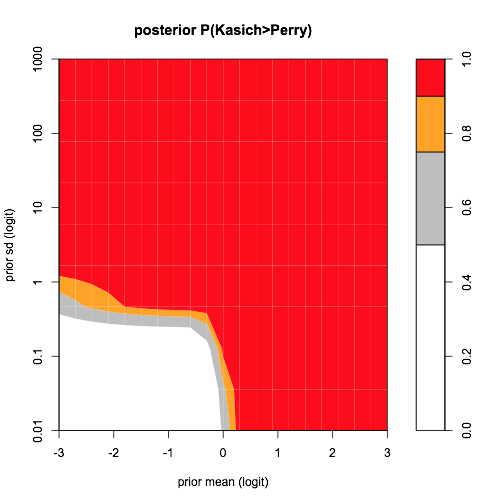

Here’s the posterior probability as a function of the prior mean and standard deviation. The red area is a posterior probability of more than 90% than Kasich is more popular (in the sense measured by opinion polls) than Perry.

In order to not have a posterior probability greater than 90%, you need either an incredibly strong prior belief that the candidates have the same popularity (sd less than about 0.1 on logit scale) or a strong prior belief that Perry was more popular.

The real weaknesses in the Fox criteria were using opinion poll scores this early in the campaign as a measure of whether someone was a serious candidate and having a ten-person debate to begin with.