NZ golf prodigy Lydia Ko has a sponsorship deal with a company that sells special jetlag-reducing water. She obviously knows how this sort of thing works, and what she said to the Herald was nicely crafted

Ms Ko said she was excited to have the support of 1Above.

“I haven’t really taken it for a long-haul flight before but I’ve seen some of the results and everything that comes with it and I have heard great things,” she said.

The reporter was also being careful about attribution

1Above contains Pycnogenol. Its makers say the natural pine bark extract is a key active ingredient in reducing the severity and length of jetlag.

I looked at the company’s web page, which has references for research papers that are supposed to support its claims. You might be interested, too. If not, this would be a good place to stop.

It’s not straightforward to find what dose is in 1Above (you’d think they would want you to know). However, a web page by someone who has used it and who was able to find some of the research papers says the 600ml bottle has 102mg of Pycnogenol. For 10 hours (the sort of flight length studied in the research) 1Above recommends 4 of their tablets, which makes two litres of drink, and so should have 340mg of Pycnogenol.

The first reference to research in people is (PubMed)

Belcaro G et al (2008). Jet lag prevention with Pycnogenol. Preliminary report: evaluation in health individualised hypertensive patients. Minerva Cardioangiol: 56 (5 Suppl):3-9

The abstract doesn’t say this was placebo-controlled. I’d ordinarily conclude it wasn’t. On the other hand, one of the other references doesn’t say in the abstract and was, so it might just be poor writing. On the other other hand, 1Above didn’t claim it was placebo-controlled, so I think it’s safe to conclude it wasn’t. I can’t tell more because the paper doesn’t appear on the website of the journal. Together with the “Suppl” in the citation information it suggests conference papers, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t peer-reviewed. The dose was 50mg of Pycnogenol three times per day for 7 days.

1Above report the results of the study, but don’t mention that it used a week of treatment (which isn’t what they recommend).

The second reference is given as

Belcaro G et al (2004). Pycnogenol® prevents thrombosis and thrombophlebitis in long-haul flights. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 10(4): 289-294

That’s the right journal and page reference, but the wrong title. The real title is a bit weaker: “Prevention of venous thrombosis and thrombophlebitis in long-haul flights with pycnogenol.”

In this case the study was placebo-controlled (though still no specific mention of randomisation or blinding of the people doing measurements). The dose was 200mg before the flight, 200mg during the flight, and 100mg the next day – a bit higher than 1Above, but not ridiculously different.

1Above says

“It has been proven to reduce and possibly even eliminate the occurrence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during flight. In a double blind Placebo study on 198 passengers, those taking Pycnogenol® supplements showed no thrombosis events as opposed to 5 reported cases in the control group”

Even if we take their word for it being double-blind, there’s a fairly dodgy slip in definitions between the first and second sentence. There were 5 measured ‘thrombotic events’ in the control group, but only one was a DVT. Also “reported” means reported by the researchers, not by the traveller – the DVT was detected by ultrasound and had not given rise to any symptoms.

The third reference is given as

Cesarone M R et al (2004). Pycnogenol® is effective against swelling of ankles during long flights based on the subjective and objective data in a double-blind, placebo controlled study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 11 (3): 289-294

Again, the right journal and page reference, but the real title is “Prevention of edema in long flights with Pycnogenol.”

This is one is also placebo-controlled, but does not say so in the abstract or in the real title. In contrast to the website, the paper doesn’t claim the study was double-blind, but they might have got that from the researchers. Swelling was lower by about half in the treated group. The dose, again, was 200mg before, 200mg during, and 100mg after.

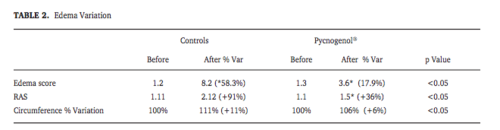

1Above uses this to justify a claim that it can reduce swelling by up to 69% of the lower limbs. I don’t know where they got that number. It’s not one of the ones in the abstract, or in this results table from the paper.

image

The final reference on relevant human research is

Belcar G (2013). Pycnogenol supplementation speeds-up recovery from a common cold, and even more efficiently in combination with vitamin C and zinv. Otorinolaringol 63: 151-161, 2013

Again, the title is wrong. The real title is “The common cold winter study: effects of Pycnogenol® on signs, symptoms, complications and costs”. Also, spelling. This one was harder to find, because the journal doesn’t seem to be in PubMed or in our library. However, there’s a post about it by a naturopath.

People who took Pycnogenol reported less symptoms. The dose was 100mg/day for the duration of the cold. It doesn’t seem to have been blinded, and it’s not clear it was randomised.

1Above cite this study to support “reduce flu like symptoms by up to 2 days”, and have a bar chart labelled “Reduce flu longevity.” The study didn’t measure flu-like symptoms. It measured common cold symptoms, and while there’s some overlap, these are different. More importantly, the study didn’t look at taking Pycnogenol in advance to prevent flu-like illness (or a cold). It looked at taking it after symptoms started, to reduce the duration. So, it would only be relevant to flying if you already have a cold before you fly.

So, on the one hand this is not very good reporting of small-scale research. You couldn’t get away with this for medications. On the other hand, it’s better than the grape extract for weight-loss company, or the one claiming to get facial reconstructions from DNA, to name a few recent examples, and it’s less likely that 1Above will do any harm that reaches beyond the wallet.

The most obvious potential problems with the research are quality of blinding (of people doing measurements) and of randomisation, which mostly weren’t mentioned.

A less obvious but potentially important problem is publication bias. According to the PubMed database, the first author of three of the references (and an author of the fourth), G. Belcaro, has 41 publications on Pycnogenol. All 41 abstracts report positive effects, across a wide range of conditions. Dr Belcaro has either been extremely lucky (in which case the results are biased by luck) or has not reported negative studies (in which case the published results are a biased sample), or has measured lots of things and put the positive results in the abstract (in which case they are again a biased sample).